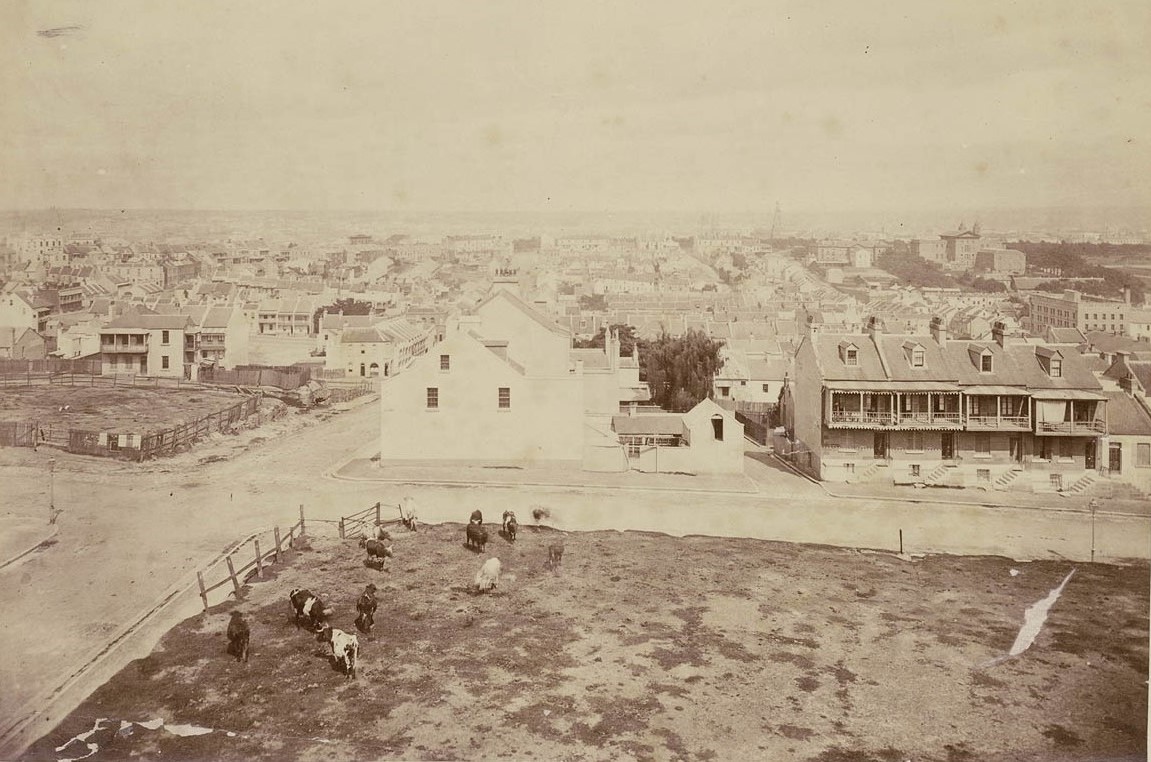

'The old Windmill, Darlinghurst', 1865-69

Near the residence of John Rae, ‘Hilton’, stereograph by Sir Hugh Dixson, State Library of NSW, DL PX 132/26

In the 1860s a series of stereograph images capture Darlinghurst as it entered a ’transition state’, from a quaint village of homesteads and paddocks, to a town lined with Victorian terraced homes. Among the vestiges of the ‘pretty hamlet’ - the crumbling cottages, grazing cows, rickety fences and creaking windmills - a sea of two to three-storey dwellings emerged.

As one rambler through the suburb observed:

In this pretty hamlet, which stands on a rocky eminence - extending, for the most part, from the precincts of Darlinghurst Gaol to hilly ground in the immediate neighbourhood of Rushcutter’s Bay… - anything like a rigid, mathematical regularity in the lines of the streets has, from the nature of the locality been impossible, so that sweeping curves, sharp corners, and mysteriously obtuse angles, here appear to be the rule instead of the exception….

Darlinghurst, on the whole, is in a transition state, and of course shares in all the drawbacks incidental to such a state, but the progress which has been made within the last few years is very gratifying to witness…and is, under every temporary disadvantage a very agreeable place for a ramble or a residence.1

Historian, Laila Ellmoos, notes that although the city’s population almost doubled in the mid-19th century and new buildings were constructed, important drainage and sewerage infrastructure lagged behind. Ellmoos concludes the City of Sydney Archives’ letters of complaint from residents not only illustrate the living conditions in these areas but the ‘intricate connections between neighbours, tenants and landlords, and how improvements in one area created problems in another’.2

Darlinghurst was also characterised by ‘absentee landlords’ and patterns of land ownership which spanned generations within single families, which resulted in a population of predominantly renters. Factors such as ownership and rental demand affected not only the type of dwellings and other buildings constructed along the street, but the fabric used in construction, lot sizes and density of the housing.3

In 1858 the economist, William Stanley Jevons, provided his analysis of the area of Darlinghurst, capturing a moment during this key development phase and revealing significant demographic features of the area, which he declared was:

…most entirely residentiary, chiefly of second class, but in some parts…with an inter-mixture of third.

The houses are mostly newly-built upon small allotments of land, and in perhaps a majority of cases are not uniform with adjoining houses in plan. The materials are nearly always brick, with only a few of rubble stone, and still fewer of wood or iron.

A large proportion of houses have two stories and four rooms, with perhaps a detached kitchen behind. Many, however, have only one story, with two or three rooms, and often the second story contains a single attic room.4

'View from 'Hilton' residence, Liverpool Street, Darlinghurst', 1879-82

Showing cattle grazing on Rae’s paddock, State Library of NSW, SPF/995

These observations are reflected in the data in the City of Sydney Archives’ Assessment Books. The 1851 book recorded three dwellings on the eastern end of Liverpool Street, including John Rae’s residence, which was listed as ’not completed’. The other two were stone dwellings with shingled roofs including Reverend Mackinson’s cottage on the corner of Liverpool and Darley streets, and a house owned and occupied by a Mr Alexander Kennedy.5

The 1855 and 1858 assessment books record 50 and 91 properties respectively. These included 45 houses, four combined houses and shops and one public house in 1855, and 61 houses, 13 dwellings and shops, three public houses, one shop and a wooden store in 1858.

In 1855, these included buildings of single-storey (13), two-storey (23) and three-storey (14), and in 1858 it was 13, 40 and 24 respectively plus two four-storey structures. In 1855 of the 50 ratepayers listed on Liverpool Street, 17 were owner occupiers.6

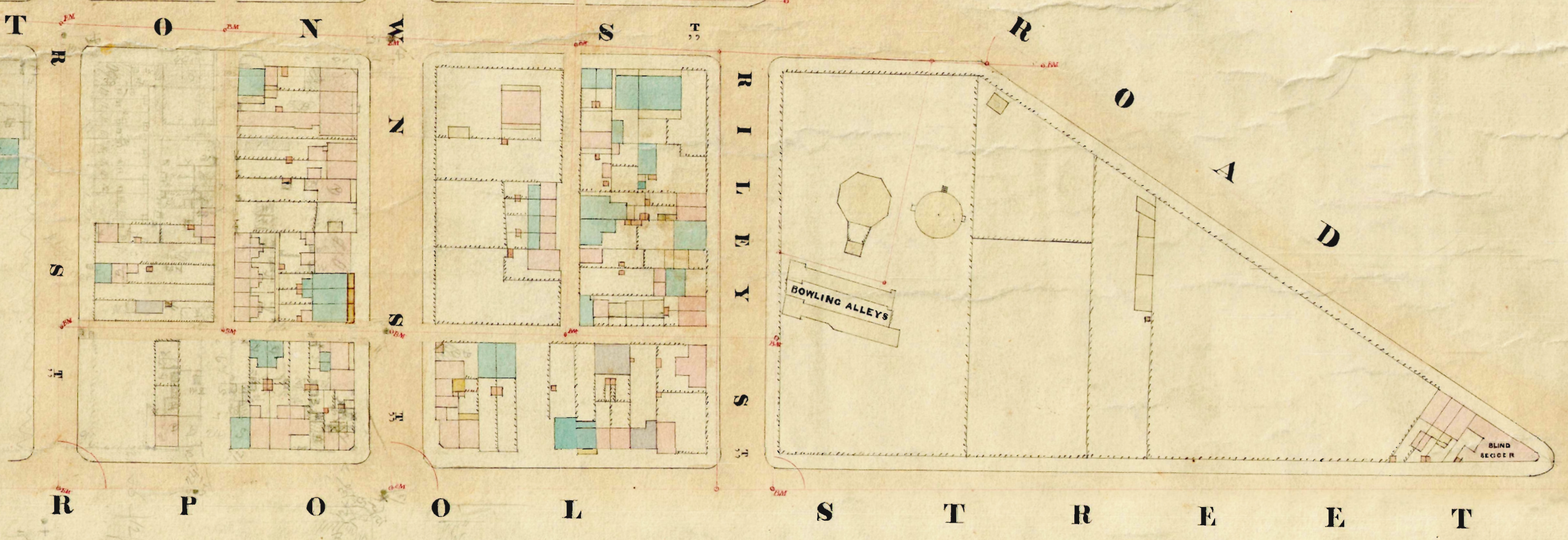

On the western end of the street from the junction of Liverpool and Oxford streets to Palmer Street, about 14 buildings are shown on one of the earliest plans of the street to survive in the City’s archives. Surveyed in 1856, it shows the majority of these were dwellings constructed of brick (shaded pink), some with stone (blue), most with outdoor water closets and some with wooden verandahs.

Detail from a survey plan of the south side of Liverpool Street between the junction of Oxford Street and Palmer Street, 1856

Showing the Blind Beggar Inn on the corner (far right) and Charles Smiths’ bowling alley facing Riley Street, surveyed by Edward Burrows, 11 February 1856, sheet 18, City of Sydney Archives, A-00880162

There were some attempts to disrupt this pattern of residential development. In 1855, Mr Charles Smith caused a stir with his ‘Places of Amusement’ on Liverpool and Riley streets. It featured an octagonal dance hall, a carousel, which he called a ‘Miniature Riding Establishment’, and an ‘American Bowling Alley’, all of which lasted just three years.

The building at the juncture of Liverpool and Oxford streets has functioned as a pub or hotel since at least 1853, when it was first established as the Blind Beggar Inn. The property was owned by the prominent merchant family, the Burdekins, and the inn was operated by publican, Henry Bradford. In 1870 it was taken over by Johnny Driscoll, a jockey and horse trainer, and it became the Terrace Hotel.7

By 1858, as seen in the data of the assessment books, the number of buildings recorded on the street had quadrupled and included hybrid buildings of 13 combined residences and shops. It was during 1860s and 1870s, that the development of the street entered a boom period and began to feature a range of dwellings and businesses.

A Flanagan's Hotel (formerly Blind Beggar Inn), c1901

Mrs Arthur George Foster, State Library of NSW, ON 146/157

Read the next part of the story.

‘Rambles through Sydney’, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 1864, 3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13085262. ↩︎

Laila Ellmoos, ‘Building Darlinghurst’ in Anna Clark, Gabrielle Kemmis and Tamson Pietsch, eds., My Darlinghurst (Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 2023), 31. ↩︎

Ellmoos, ‘Building Darlinghurst’ in My Darlinghurst, 31. ↩︎

‘Sydney in 1858’, Sydney Morning Herald, 16 November 1929, 13, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16602243. ↩︎

Assessment Book - Cook Ward, 1851 (01/01/1851 - 31/12/1851), [A-01089356], City of Sydney Archives, https://archives.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nodes/view/1842248. ↩︎

Assessment Book - Fitzroy Ward, 1855 (01/01/1855 - 31/12/1855), [A-01089285]. City of Sydney Archives, https://archives.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nodes/view/1842177, Assessment Book - Fitzroy Ward, 1858 (01/01/1858 - 31/12/1858), [A-01089284]. City of Sydney Archives, https://archives.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nodes/view/1842176 and Assessment Book - Cook Ward, 1858 (01/01/1858 - 31/12/1858), [A-01089354]. City of Sydney Archives, https://archives.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nodes/view/1842246. ↩︎

‘City Council’, Sydney Morning Herald, 20 December 1853, 5, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12953640 and ‘Tuse Talk’, Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Chronicle, 12 November 1870, 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65473097. ↩︎