The place where the rushes grow

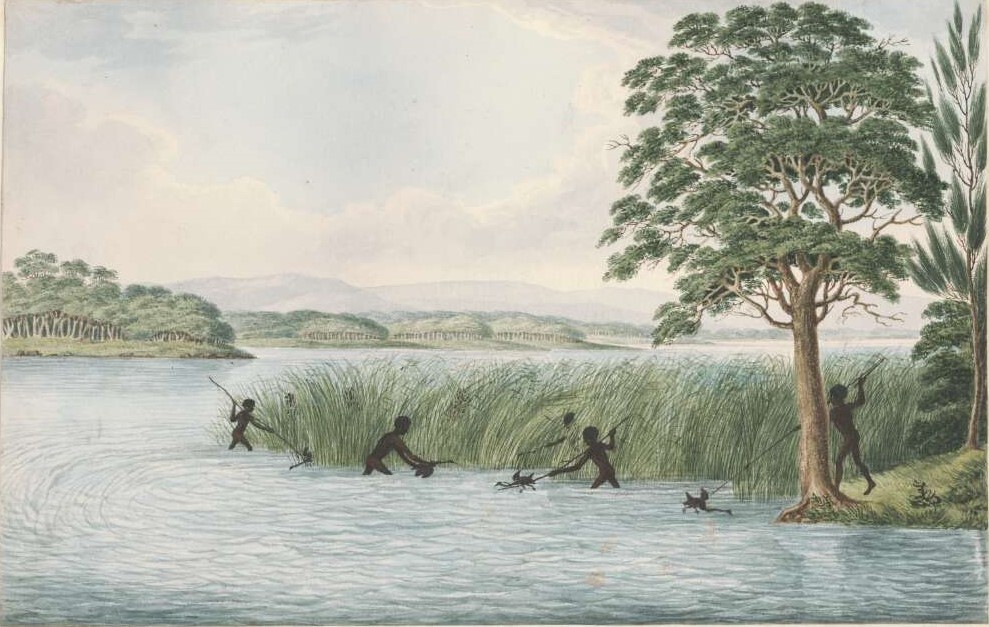

Aboriginal people hunting waterbirds among the rushes, c1817

Joseph Lycett in Drawings of Aborigines and scenery, New South Wales, National Library of Australia

Kogerah was a place where blackbutt, red gum trees and others stood tall and in abundance, like quiet sentinels surveying a pristine harbour. Believed to mean ‘place where the rushes grow’, Kogerah was and is Gadigal Country.1

For generations the Gadigal people and their neighbouring Sydney clans expertly fished the harbour aboard nawi (bark canoes) and speared maugro (fish) from the shore with garrara (pronged spears).

Sometimes, they lay across their nawi, motionless, their faces in the water looking for fish and spears ready for ‘darting’.2

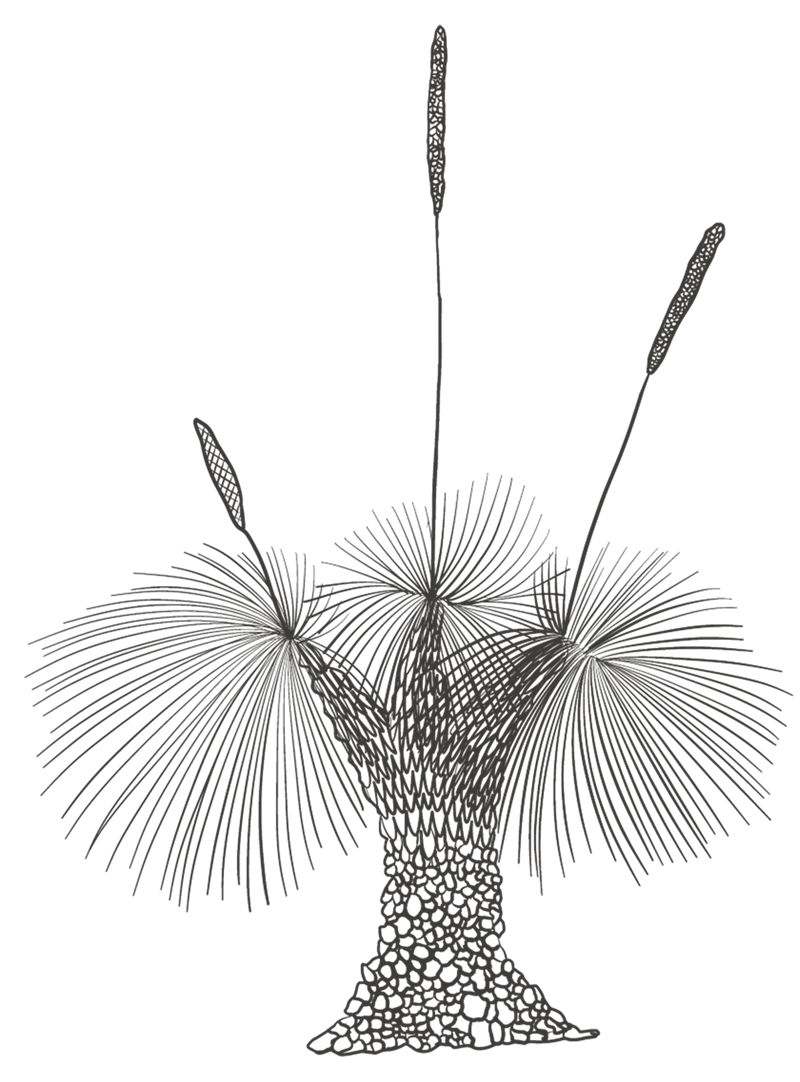

Goolgadie, the grasstree from which the word Gadigal is derived, provided both food and raw materials: nectar from its flowers, its flowering stem as spear shafts, resin as an adhesive, and fronds for headdresses.3

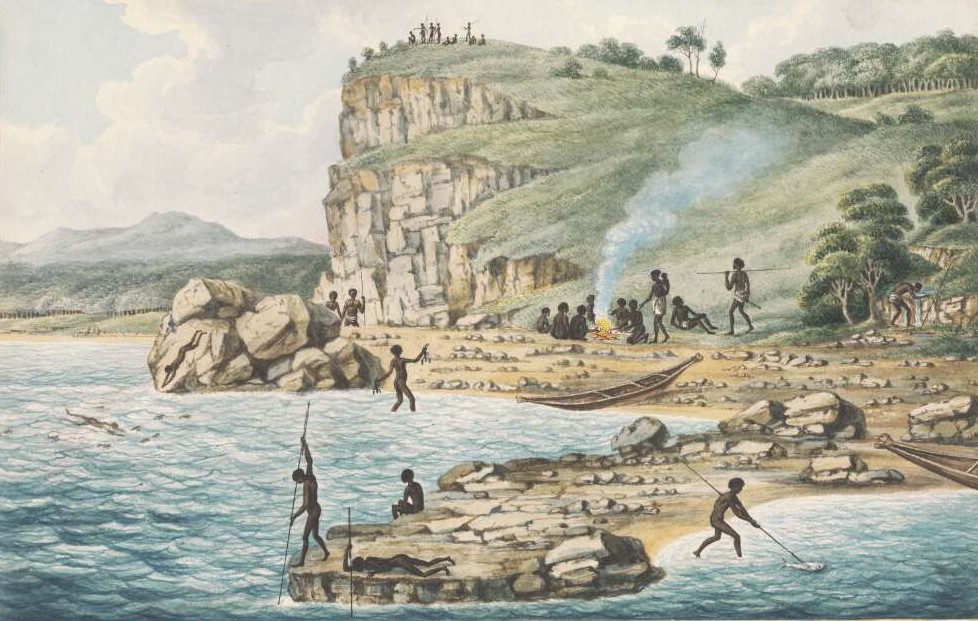

Aboriginal people spearing fish and diving for shellfish, c1817

Joseph Lycett in Drawings of Aborigines and scenery, New South Wales, National Library of Australia

The women, often with children in tow, used burra (shell hooks) which they flung into the water attached to carr-e-jun (fishing lines). Aboard their nawi, they sang as they reeled in their catch and cooked over small fires laid aboard on seaweed or sand. Their nawi were among their most treasured possessions, as tools for survival and a means of connection with Country.4

They used rock-shelters and built bark huts close to freshwater streams. They hunted kangaroos, wallabies and other land mammals. They collected kaadian (Sydney cockle), badangi (rock oyster), dalgal (mussel), and other shellfish.

A stream of clear, fresh water cut through Kogerah, pooling and cascading before it reached mudflats and flowed into the bay. It was part of many wetland systems across Sydney, which extended south, far beyond this area, and drained into Kamay (Botany Bay).5

This system sustained a variety of life:

It swarmed with aquatic birds of every description, red bills, water hens, bitterns, quail, frequently all kinds of ducks, and, when in season, snipe and landrails, and at all times bronze-winged pigeons could be had in abundance.

Brush wallabies were also very numerous in the vicinity….the head of the swamp was a great resort for dingoes.6

Read the next part of the story.

Variously spelt Kogerrah, Kogarah, Cuggerah, Koggerah. Obed West, ‘Old and New Sydney: XIX Our Harbour and Ocean Bays’, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 October 1882, 9, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13522182; ‘Rushcutters Bay’, Geographical Names Board, NSW Government, gazetted 19 November 1976; ‘Port Jackson Aboriginal Names’, Science of Man 12, no. 1 (1 June 1910), 35, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-520313745; Valerie Attenbrow, Sydney’s Aboriginal Past: Investigating the archaeological and historical records (Sydney, NSW: University of New South Wales Press Ltd, 2010), 11. The word Kogerah has not been adopted as a dual name for Rushcutters Bay due to its potential to cause confusion with the southern Sydney suburb of Kogarah, see Jakelin Troy and Michael Walsh, ‘Reinstating Aboriginal placenames around Port Jackson and Botany Bay’ in Harold Koch and Luise Hercus eds., Aboriginal Placenames: Naming and re-naming the Australian landscape (Canberra, ACT: ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc., 2009). ↩︎

‘John Hunter journal kept on board the Sirius during a voyage to New South Wales’, May 1787-March 1791, 86-87, State Library of NSW, SAFE/DLMS 164, John Hunter, second captain on board the First Fleet flagship, HMS Sirius, and later second Governor of New South Wales, witnessed ‘a man laying across a Canoe with his face in the water, & his fish Gig [spear] immers’d ready for darting; in this Manner he lays Motionless, & by his face being a little under the Surface he can see the fish distinctly….’ See also Jakelin Troy, The Sydney Language (Canberra, ACT: Aboriginal Studies Press, reprinted 2019), 44. ↩︎

Attenbrow, Sydney’s Aboriginal Past, figure 6, 63 and 67 and Troy, Sydney Language, 61. ↩︎

Attenbrow, Sydney’s Aboriginal Past, 63; Troy, Sydney Language, 44; Keith Vincent Smith, ‘Big Canoes’ in Mari Nawi: Aboriginal Odysseys 1790-1850 (Sydney, NSW: State Library of New South Wales, 2010), 5 and Grace Karskens, ‘Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2014, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/index.php/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen. ↩︎

Troy, Sydney Language, 58-59; Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2010), 19 and Paul Irish, ‘Aboriginal Paddington’ in Paddington: A History, edited by Greg Young (Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 2019), 20. ↩︎

West, ‘Old and New Sydney’, 9, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13522182. ↩︎